by Maria Popova

“The people we most love do become a physical part

of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are

created.”

John Updike

wrote in his memoir,

“Each

day, we wake slightly altered, and the person we were yesterday is

dead. So why, one could say, be afraid of death, when death comes all

the time?” And yet even if we were to somehow make peace with

our own mortality,

a primal and soul-shattering fear rips through whenever we think about

losing those we love most dearly — a fear that metastasizes into

all-consuming grief when loss does come. In

The Long Goodbye (

public library), her magnificent memoir of grieving her mother’s death,

Meghan O’Rourke

crafts a masterwork of remembrance and reflection woven of

extraordinary emotional intelligence. A poet, essayist, literary critic,

and one of the youngest editors the

New Yorker has ever had,

she tells a story that is deeply personal in its details yet richly

resonant in its larger humanity, making tangible the messy and often

ineffable complexities that anyone who has ever lost a loved one knows

all too intimately, all too anguishingly. What makes her writing — her

mind, really — particularly enchanting is that she brings to this

paralyzingly difficult subject a poet’s emotional precision, an

essayist’s intellectual expansiveness, and a voracious reader’s gift for

apt, exquisitely placed allusions to such luminaries of language and

life as Whitman, Longfellow, Tennyson, Swift, and Dickinson (“the

supreme poet of grief”).

O’Rourke writes:

When we are learning the world, we know things we cannot

say how we know. When we are relearning the world in the aftermath of a

loss, we feel things we had almost forgotten, old things, beneath the

seat of reason.

[…]

Nothing prepared me for the loss of my mother. Even knowing that she

would die did not prepare me. A mother, after all, is your entry into

the world. She is the shell in which you divide and become a life.

Waking up in a world without her is like waking up in a world without

sky: unimaginable.

[…]

When we talk about love, we go back to the start, to pinpoint the

moment of free fall. But this story is the story of an ending, of death,

and it has no beginning. A mother is beyond any notion of a beginning.

That’s what makes her a mother: you cannot start the story.

In the days following her mother’s death, as O’Rourke faces the

loneliness she anticipated and the sense of being lost that engulfed her

unawares, she contemplates the paradoxes of loss: Ours is a culture

that treats grief — a process of profound emotional upheaval — with a

grotesquely mismatched rational prescription. On the one hand, society

seems to operate by a set of unspoken shoulds for how we ought to feel

and behave in the face of sorrow; on the other, she observes, “we have

so few rituals for observing and externalizing loss.” Without a coping

strategy, she finds herself shutting down emotionally and going “dead

inside” — a feeling psychologists call “numbing out” — and describes the

disconnect between her intellectual awareness of sadness and its

inaccessible emotional manifestation:

It was like when you stay in cold water too long. You know something is off but don’t start shivering for ten minutes.

But at least as harrowing as the aftermath of loss is the

anticipatory bereavement in the months and weeks and days leading up to

the inevitable — a particularly cruel reality of terminal cancer.

O’Rourke writes:

So much of dealing with a disease is waiting. Waiting for

appointments, for tests, for “procedures.” And waiting, more broadly,

for it—for the thing itself, for the other shoe to drop.

The hallmark of this anticipatory loss seems to be a tapestry of

inner contradictions. O’Rourke notes with exquisite self-awareness her

resentment for the mundanity of it all — there is her mother, sipping

soda in front of the TV on one of those final days — coupled with

weighty, crushing compassion for the sacred humanity of death:

Time doesn’t obey our commands. You cannot make it holy just because it is disappearing.

Then there was the question of the body — the object of so much

social and personal anxiety in real life, suddenly stripped of control

in the surreal experience of impending death. Reflecting on the

initially disorienting experience of helping her mother on and off the

toilet and how quickly it became normalized, O’Rourke writes:

It was what she had done for us, back before we became

private and civilized about our bodies. In some ways I liked it. A level

of anxiety about the body had been stripped away, and we were left with

the simple reality: Here it was.

I heard a lot about the idea of dying “with dignity” while my mother

was sick. It was only near her very end that I gave much thought to what

this idea meant. I didn’t actually feel it was undignified for my

mother’s body to fail — that was the human condition. Having to help my

mother on and off the toilet was difficult, but it was natural. The real

indignity, it seemed, was dying where no one cared for you the way your

family did, dying where it was hard for your whole family to be with

you and where excessive measures might be taken to keep you alive past a

moment that called for letting go. I didn’t want that for my mother. I

wanted her to be able to go home. I didn’t want to pretend she wasn’t

going to die.

Among the most painful realities of witnessing death — one

particularly exasperating for type-A personalities — is how swiftly it

severs the direct correlation between effort and outcome around which we

build our lives. Though the notion might seem rational on the surface —

especially in a culture that fetishizes work ethic and

“grit” as the key to success

— an underbelly of magical thinking lurks beneath, which comes to light

as we behold the helplessness and injustice of premature death. Noting

that “the mourner’s mind is superstitious, looking for signs and

wonders,” O’Rourke captures this paradox:

One of the ideas I’ve clung to most of my life is that if

I just try hard enough it will work out. If I work hard, I will be

spared, and I will get what I desire, finding the cave opening over and

over again, thieving life from the abyss. This sturdy belief system has a

sidecar in which superstition rides. Until recently, I half believed

that if a certain song came on the radio just as I thought of it, it

meant that all would be well. What did I mean? I preferred not to answer

that question. To look too closely was to prick the balloon of

possibility.

But our very capacity for the irrational — for the magic of magical

thinking — also turns out to be essential for our spiritual survival.

Without the capacity to discern from life’s senseless sound a meaningful

melody, we would be consumed by the noise. In fact, one of O’Rourke’s

most poetic passages recounts her struggle to find a transcendent

meaning on an average day, amid the average hospital noises:

I could hear the coughing man whose family talked about

sports and sitcoms every time they visited, sitting politely around his

bed as if you couldn’t see the death knobs that were his knees poking

through the blanket, but as they left they would hug him and say, We

love you, and We’ll be back soon, and in their voices and in mine and in

the nurse who was so gentle with my mother, tucking cool white sheets

over her with a twist of her wrist, I could hear love, love that sounded

like a rope, and I began to see a flickering electric current

everywhere I looked as I went up and down the halls, flagging nurses,

little flecks of light dotting the air in sinewy lines, and I leaned on

these lines like guy ropes when I was so tired I couldn’t walk anymore

and a voice in my head said: Do you see this love? And do you still not believe?

I couldn’t deny the voice.

Now I think: That was exhaustion.

But at the time the love, the love, it was like ropes around me,

cables that could carry us up into the higher floors away from our

predicament and out onto the roof and across the empty spaces above the

hospital to the sky where we could gaze down upon all the people

driving, eating, having sex, watching TV, angry people, tired people,

happy people, all doing, all being –

In the weeks following her mother’s death, melancholy — “the black

sorrow, bilious, angry, a slick in my chest” — comes coupled with

another intense emotion, a parallel longing for a different branch of

that-which-no-longer-is:

I experienced an acute nostalgia. This longing for a lost

time was so intense I thought it might split me in two, like a tree hit

by lightning. I was — as the expression goes — flooded by memories. It

was a submersion in the past that threatened to overwhelm any “rational”

experience of the present, water coming up around my branches, rising

higher. I did not care much about work I had to do. I was consumed by

memories of seemingly trivial things.

But the embodied presence of the loss is far from trivial. O’Rourke,

citing a psychiatrist whose words had stayed with her, captures it with

harrowing precision:

The people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.

In another breathtaking passage, O’Rourke conveys the largeness of

grief as it emanates out of our pores and into the world that surrounds

us:

In February, there was a two-day snowstorm in New York.

For hours I lay on my couch, reading, watching the snow drift down

through the large elm outside … the sky going gray, then eerie violet,

the night breaking around us, snow like flakes of ash. A white mantle

covered trees, cars, lintels, and windows. It was like one of grief’s

moods: melancholic; estranged from the normal; in touch with the longing

that reminds us that we are being-toward-death, as Heidegger puts it.

Loss is our atmosphere; we, like the snow, are always falling toward the

ground, and most of the time we forget it.

Because grief seeps into the external world as the inner experience

bleeds into the outer, it’s understandable — it’s hopelessly human —

that we’d also project the very object of our grief onto the external

world. One of the most common experiences, O’Rourke notes, is for the

grieving to try to bring back the dead — not literally, but by seeing,

seeking, signs of them in the landscape of life, symbolism in the

everyday. The mind, after all, is a pattern-recognition machine and when

the mind’s eye is as heavily clouded with a particular object as it is

when we grieve a loved one, we begin to manufacture patterns. Recounting

a day when she found inside a library book handwriting that seemed to

be her mother’s, O’Rourke writes:

The idea that the dead might not be utterly gone has an

irresistible magnetism. I’d read something that described what I had

been experiencing. Many people go through what psychologists call a

period of “animism,” in which you see the dead person in objects and

animals around you, and you construct your false reality, the reality

where she is just hiding, or absent. This was the mourner’s secret

position, it seemed to me: I have to say this person is dead, but I don’t have to believe it.

[…]

Acceptance isn’t necessarily something you can choose off a menu,

like eggs instead of French toast. Instead, researchers now think that

some people are inherently primed to accept their own death with

“integrity” (their word, not mine), while others are primed for

“despair.” Most of us, though, are somewhere in the middle, and one

question researchers are now focusing on is: How might more of those in

the middle learn to accept their deaths? The answer has real

consequences for both the dying and the bereaved.

O’Rourke considers the psychology and physiology of grief:

When you lose someone you were close to, you have to

reassess your picture of the world and your place in it. The more your

identity is wrapped up with the deceased, the more difficult the mental

work.

The first systematic survey of grief, I read, was conducted by Erich

Lindemann. Having studied 101 people, many of them related to the

victims of the Cocoanut Grove fire of 1942, he defined grief as

“sensations of somatic distress occurring in waves lasting from twenty

minutes to an hour at a time, a feeling of tightness in the throat,

choking with shortness of breath, need for sighing, and an empty feeling

in the abdomen, lack of muscular power, and an intensive subjective

distress described as tension or mental pain.”

Tracing the history of studying grief, including Elisabeth

Kübler-Ross’s famous and often criticized 1969 “stage theory” outlining a

simple sequence of Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and

Acceptance, O’Rourke notes that most people experience grief not as

sequential stages but as ebbing and flowing states that recur at various

points throughout the process. She writes:

Researchers now believe there are two kinds of grief:

“normal grief” and “complicated grief” (also called “prolonged grief”).

“Normal grief” is a term for what most bereaved people experience. It

peaks within the first six months and then begins to dissipate.

“Complicated grief” does not, and often requires medication or therapy.

But even “normal grief” … is hardly gentle. Its symptoms include

insomnia or other sleep disorders, difficulty breathing, auditory or

visual hallucinations, appetite problems, and dryness of mouth.

One of the most persistent psychiatric ideas about grief, O’Rourke

notes, is the notion that one ought to “let go” in order to “move on” — a

proposition plentiful even in the casual advice of her friends in the

weeks following her mother’s death. And yet it isn’t necessarily the

right coping strategy for everyone, let alone the only one, as our

culture seems to suggest. Unwilling to “let go,” O’Rourke finds solace

in anthropological alternatives:

Studies have shown that some mourners hold on to a

relationship with the deceased with no notable ill effects. In China,

for instance, mourners regularly speak to dead ancestors, and one study

demonstrated that the bereaved there “recovered more quickly from loss”

than bereaved Americans do.

I wasn’t living in China, though, and in those weeks after my

mother’s death, I felt that the world expected me to absorb the loss and

move forward, like some kind of emotional warrior. One night I heard a

character on 24—the president of the United States—announce that grief

was a “luxury” she couldn’t “afford right now.” This model represents an

old American ethic of muscling through pain by throwing yourself into

work; embedded in it is a desire to avoid looking at death. We’ve

adopted a sort of “Ask, don’t tell” policy. The question “How are you?”

is an expression of concern, but as my dad had said, the mourner quickly

figures out that it shouldn’t always be taken for an actual inquiry… A

mourner’s experience of time isn’t like everyone else’s. Grief that

lasts longer than a few weeks may look like self-indulgence to those

around you. But if you’re in mourning, three months seems like nothing —

[according to some] research, three months might well find you

approaching the height of sorrow.

Another Western hegemony in the culture of grief, O’Rourke notes, is

its privatization — the unspoken rule that mourning is something we do

in the privacy of our inner lives, alone, away from the public eye.

Though for centuries private grief was externalized as public mourning,

modernity has left us bereft of rituals to help us deal with our grief:

The disappearance of mourning rituals affects everyone,

not just the mourner. One of the reasons many people are unsure about

how to act around a loss is that they lack rules or meaningful

conventions, and they fear making a mistake. Rituals used to help the

community by giving everyone a sense of what to do or say. Now, we’re at

sea.

[…]

Such rituals … aren’t just about the individual; they are about the community.

Craving “a formalization of grief, one that might externalize it,” O’Rourke plunges into the existing literature:

The British anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer, the author of Death, Grief, and Mourning,

argues that, at least in Britain, the First World War played a huge

role in changing the way people mourned. Communities were so overwhelmed

by the sheer number of dead that the practice of ritualized mourning

for the individual eroded. Other changes were less obvious but no less

important. More people, including women, began working outside the home;

in the absence of caretakers, death increasingly took place in the

quarantining swaddle of the hospital. The rise of psychoanalysis shifted

attention from the communal to the individual experience. In 1917, only

two years after Émile Durkheim wrote about mourning as an essential

social process, Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” defined it as

something essentially private and individual, internalizing the work of

mourning. Within a few generations, I read, the experience of grief had

fundamentally changed. Death and mourning had been largely removed from

the public realm. By the 1960s, Gorer could write that many people

believed that “sensible, rational men and women can keep their mourning

under complete control by strength of will and character, so that it

need be given no public expression, and indulged, if at all, in private,

as furtively as . . . masturbation.” Today, our only public mourning

takes the form of watching the funerals of celebrities and statesmen.

It’s common to mock such grief as false or voyeuristic (“crocodile

tears,” one commentator called mourners’ distress at Princess Diana’s

funeral), and yet it serves an important social function. It’s a more

mediated version, Leader suggests, of a practice that goes all the way

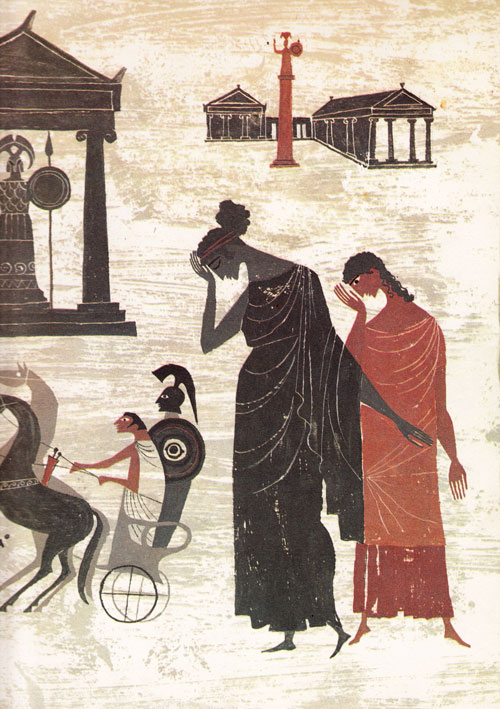

back to soldiers in The Iliad mourning with Achilles for the fallen Patroclus.

I found myself nodding in recognition at Gorer’s conclusions. “If

mourning is denied outlet, the result will be suffering,” Gorer wrote.

“At the moment our society is signally failing to give this support and

assistance. . . . The cost of this failure in misery, loneliness,

despair and maladaptive behavior is very high.” Maybe it’s not a

coincidence that in Western countries with fewer mourning rituals, the

bereaved report more physical ailments in the year following a death.

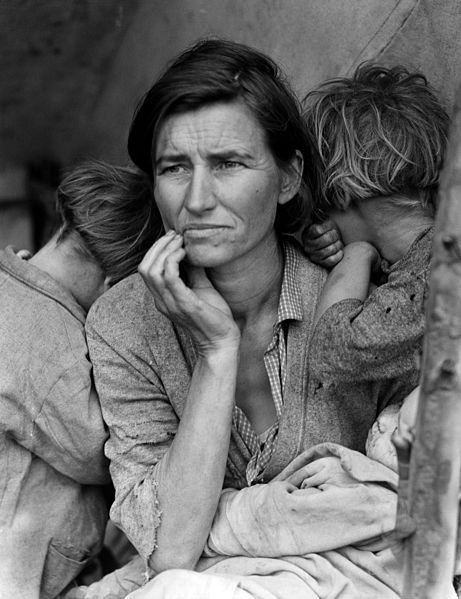

Illustration from 'The Iliad and the Odyssey: A Giant Golden Book' by Alice and Martin Provensen. Click image for details.

Finding solace in

Marilynne Robinson’s beautiful meditation on our humanity, O’Rourke returns to her own journey:

The otherworldliness of loss was so intense that at times

I had to believe it was a singular passage, a privilege of some kind,

even if all it left me with was a clearer grasp of our human

predicament. It was why I kept finding myself drawn to the remote

desert: I wanted to be reminded of how the numinous impinges on ordinary

life.

Reflecting on her struggle to accept her mother’s loss — her absence, “an absence that becomes a presence” — O’Rourke writes:

If children learn through exposure to new experiences, mourners unlearn

through exposure to absence in new contexts. Grief requires acquainting

yourself with the world again and again; each “first” causes a break

that must be reset… And so you always feel suspense, a queer dread—you

never know what occasion will break the loss freshly open.

She later adds:

After a loss, you have to learn to believe the dead one is dead. It doesn’t come naturally.

Among the most chilling effects of grief is how it reorients us toward ourselves as it surfaces our

mortality paradox

and the dawning awareness of our own impermanence. O’Rourke’s words

ring with the profound discomfort of our shared existential bind:

The dread of death is so primal, it overtakes me on a

molecular level. In the lowest moments, it produces nihilism. If I am

going to die, why not get it over with? Why live in this agony of

anticipation?

[…]

I was unable to push these questions aside: What are we to do with

the knowledge that we die? What bargain do you make in your mind so as

not to go crazy with fear of the predicament, a predicament none of us

knowingly chose to enter? You can believe in God and heaven, if you have

the capacity for faith. Or, if you don’t, you can do what a stoic like

Seneca did, and push away the awfulness by noting that if death is

indeed extinction, it won’t hurt, for we won’t experience it. “It would

be dreadful could it remain with you; but of necessity either it does

not arrive or else it departs,” he wrote.

If this logic fails to comfort, you can decide, as Plato and Jonathan

Swift did, that since death is natural, and the gods must exist, it

cannot be a bad thing. As Swift said, “It is impossible that anything so

natural, so necessary, and so universal as death, should ever have been

designed by Providence as an evil to mankind.” And Socrates: “I am

quite ready to admit … that I ought to be grieved at death, if I were

not persuaded in the first place that I am going to other gods who are

wise and good.” But this is poor comfort to those of us who have no gods

to turn to. If you love this world, how can you look forward to

departing it? Rousseau wrote, “He who pretends to look on death without

fear lies. All men are afraid of dying, this is the great law of

sentient beings, without which the entire human species would soon be

destroyed.”

And yet, O’Rourke arrives at the same conclusion that Alan Lightman did in his

sublime meditation on our longing for permanence as she writes:

Without death our lives would lose their shape: “Death is

the mother of beauty,” Wallace Stevens wrote. Or as a character in Don

DeLillo’s White Noise says, “I think it’s a mistake to lose

one’s sense of death, even one’s fear of death. Isn’t death the boundary

we need?” It’s not clear that DeLillo means us to agree, but I think I

do. I love the world more because it is transient.

[…]

One would think that living so proximately to the provisional would

ruin life, and at times it did make it hard. But at other times I

experienced the world with less fear and more clarity. It didn’t matter

if I was in line for an extra two minutes. I could take in the

sensations of color, sound, life. How strange that we should live on

this planet and make cereal boxes, and shopping carts, and gum! That we

should renovate stately old banks and replace them with Trader Joe’s! We

were ants in a sugar bowl, and one day the bowl would empty.

A Perseid meteor over Joshua Tree National Park (Image: Joe Westerberg / NASA)

This awareness of our transience, our minuteness, and the paradoxical

enlargement of our aliveness that it produces seems to be the sole

solace from grief’s grip, though we all arrive at it differently.

O’Rourke’s father approached it from another angle. Recounting a

conversation with him one autumn night — one can’t help but notice the

beautiful, if inadvertent, echo of

Carl Sagan’s memorable words — O’Rourke writes:

“The Perseid meteor showers are here,” he told me. “And

I’ve been eating dinner outside and then lying in the lounge chairs

watching the stars like your mother and I used to” — at some point he

stopped calling her Mom — “and that helps. It might sound strange, but I

was sitting there, looking up at the sky, and I thought, ‘You are but a

mote of dust. And your troubles and travails are just a mote of a mote

of dust.’ And it helped me. I have allowed myself to think about things I

had been scared to think about and feel. And it allowed me to be there —

to be present. Whatever my life is, whatever my loss is, it’s small in

the face of all that existence… The meteor shower changed something. I

was looking the other way through a telescope before: I was just looking

at what was not there. Now I look at what is there.”

O’Rourke goes on to reflect on this ground-shifting quality of loss:

It’s not a question of getting over it or healing. No;

it’s a question of learning to live with this transformation. For the

loss is transformative, in good ways and bad, a tangle of change that

cannot be threaded into the usual narrative spools. It is too central

for that. It’s not an emergence from the cocoon, but a tree growing

around an obstruction.

In one of the most beautiful passages in the book, O’Rourke captures

the spiritual sensemaking of death in an anecdote that calls to mind

Alan Lightman’s account of a “transcendent experience” and Alan Watt’s

consolation in the oneness of the universe. She writes:

Before we scattered the ashes, I had an eerie experience.

I went for a short run. I hate running in the cold, but after so much

time indoors in the dead of winter I was filled with exuberance. I ran

lightly through the stripped, bare woods, past my favorite house, poised

on a high hill, and turned back, flying up the road, turning left. In

the last stretch I picked up the pace, the air crisp, and I felt myself

float up off the ground. The world became greenish. The brightness of

the snow and the trees intensified. I was almost giddy. Behind the

bright flat horizon of the treescape, I understood, were worlds beyond

our everyday perceptions. My mother was out there, inaccessible to me,

but indelible. The blood moved along my veins and the snow and trees

shimmered in greenish light. Suffused with joy, I stopped stock-still in

the road, feeling like a player in a drama I didn’t understand and

didn’t need to. Then I sprinted up the driveway and opened the door and

as the heat rushed out the clarity dropped away.

I’d had an intuition like this once before, as a child in Vermont. I

was walking from the house to open the gate to the driveway. It was

fall. As I put my hand on the gate, the world went ablaze, as bright as

the autumn leaves, and I lifted out of myself and understood that I was

part of a magnificent book. What I knew as “life” was a thin version of

something larger, the pages of which had all been written. What I would

do, how I would live — it was already known. I stood there with a kind

of peace humming in my blood.

A non-believer who had prayed for the first time in her life when her mother died, O’Rourke quotes Virginia Woolf’s

luminous meditation on the spirit and writes:

This is the closest description I have ever come across

to what I feel to be my experience. I suspect a pattern behind the wool,

even the wool of grief; the pattern may not lead to heaven or the

survival of my consciousness — frankly I don’t think it does — but that

it is there somehow in our neurons and synapses is evident to

me. We are not transparent to ourselves. Our longings are like thick

curtains stirring in the wind. We give them names. What I do not know is

this: Does that otherness — that sense of an impossibly real universe

larger than our ability to understand it — mean that there is meaning

around us?

[…]

I have learned a lot about how humans think about death. But it

hasn’t necessarily taught me more about my dead, where she is, what she

is. When I held her body in my hands and it was just black ash, I felt

no connection to it, but I tell myself perhaps it is enough to still be

matter, to go into the ground and be “remixed” into some new part of the

living culture, a new organic matter. Perhaps there is some solace in

this continued existence.

[…]

I think about my mother every day, but not as concertedly as I used

to. She crosses my mind like a spring cardinal that flies past the edge

of your eye: startling, luminous, lovely, gone.

The Long Goodbye

is a remarkable read in its entirety — the kind that speaks with gentle

crispness to the parts of us we protect most fiercely yet long to

awaken most desperately. Complement it with

Alan Lightman in finding solace in our impermanence and

Tolstoy on finding meaning in a meaningless world.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours

each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider

becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly

donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

Satchin Panda (right)

is one of these scientists. A professor of molecular biology, he works

at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California,

where he does research on the body clock that every living being has

inside them. “My grandpa was almost religious about taking an hour’s nap

by day,” says Panda. “He slept nine to ten hours a night.” Such habits

would be inconceivable for Panda himself. But he is far from complacent

about the contrast between their lives: he fears that when we override

the light-dark cycle of the natural world, we are disrupting the

internal workings of the human body. By robbing ourselves of daylight we

may be losing something more fundamental.

Satchin Panda (right)

is one of these scientists. A professor of molecular biology, he works

at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California,

where he does research on the body clock that every living being has

inside them. “My grandpa was almost religious about taking an hour’s nap

by day,” says Panda. “He slept nine to ten hours a night.” Such habits

would be inconceivable for Panda himself. But he is far from complacent

about the contrast between their lives: he fears that when we override

the light-dark cycle of the natural world, we are disrupting the

internal workings of the human body. By robbing ourselves of daylight we

may be losing something more fundamental.

Daylight

is not intrinsically better for us than electric light, Figueiro says.

It’s just that getting artificial light to do the same job “is more

expensive, uses more energy and is more difficult to get right”. But

getting it right is exactly what she’s aiming to do.

Daylight

is not intrinsically better for us than electric light, Figueiro says.

It’s just that getting artificial light to do the same job “is more

expensive, uses more energy and is more difficult to get right”. But

getting it right is exactly what she’s aiming to do.